Walking through a valley nobody has ever been, attempting an unclimbed peak – First ascents, exploration in the spirit and style of Mallory & Buhl, to face the obstacles of the unknown has been a dream of mine….for a long, long time!  Over the last few weeks that dream came true by being part of an Austro-Australian team that ventured in a remote corner of eastern Tibet – the Shaluli Shan range and the prominent Central Gangga massif. Our expedition had everything – avalanches, rockfall, great food, heavy snowfall, steep ascents, difficult rock and crappy rotten ice. The team met in Chengdu: Judith and Gerald, my climbing buddies from Austria (earlier this year we had attempted Mont Bland and ended scaling Gran Paradiso (https://dev.neilmatthews.com/paulniel/a-strangled-madonna-che-guevara-and-a-few-daisies/)), Ed from Tokyo, who I met on Mt Fuji last year and with whom the idea was born, Rob my tent buddy from Perth and “Two Chaps” Dan from Sydney.

Over the last few weeks that dream came true by being part of an Austro-Australian team that ventured in a remote corner of eastern Tibet – the Shaluli Shan range and the prominent Central Gangga massif. Our expedition had everything – avalanches, rockfall, great food, heavy snowfall, steep ascents, difficult rock and crappy rotten ice. The team met in Chengdu: Judith and Gerald, my climbing buddies from Austria (earlier this year we had attempted Mont Bland and ended scaling Gran Paradiso (https://dev.neilmatthews.com/paulniel/a-strangled-madonna-che-guevara-and-a-few-daisies/)), Ed from Tokyo, who I met on Mt Fuji last year and with whom the idea was born, Rob my tent buddy from Perth and “Two Chaps” Dan from Sydney.  Chengdu on first glance was the prototype Chinese metropolis – shiny new buildings, spicy food (its Sichuan cuisine after all!) and grey, always grey sky. It all about the pandas and we managed to see enough for a lifetime in the Panda research centre on the outskirts of town (yeah, they were cute, very cute! ….but lazy!).

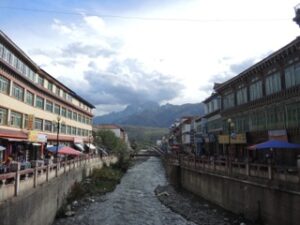

Chengdu on first glance was the prototype Chinese metropolis – shiny new buildings, spicy food (its Sichuan cuisine after all!) and grey, always grey sky. It all about the pandas and we managed to see enough for a lifetime in the Panda research centre on the outskirts of town (yeah, they were cute, very cute! ….but lazy!).  Having enjoyed a last shower and a final toilet seat, we drove for two very bumpy days westwards. The road led along the northern Sichuan- Tibet Highway to the small provincial town of Ganzi. Here was the last stop before the mountains where our local support crew, translator Alex and cook Pan bought the last supplies for base camp. From the roof of our hotel, we could already see the towering mountain of the central Ganga, and its highest peak ….. Well, what was its name? Our permit, formally given by the Chinese Mountaineering authority, the peak was defined as Mt Wuming (?!), but this was just a placeholder the authorities use for every peak that doesn’t have a name. As one could see the peak from almost everywhere in town I thought it impossible that it hadn’t got a name – equipped with the chinese phrase of (“Whats the name of this mountain?”) I went through town interviewing people and had to realize: a) there weren’t a lot of people in town that speak chinese – culturally this part of Sichuan belongs to Tibet, and most people I met didn’t want to write or speak Chinese b) that my questions tons usually ended in a ton of laughter or utter confusion c) and that only a very old woman, after a lengthy discussion (the topic of which I would obviously not know, as it was in a language unfamiliar to me) scribbled the word “Zhouda” into my notebook. So there we were – on our route to Zhouda-shan (Mt Zhouda).

Having enjoyed a last shower and a final toilet seat, we drove for two very bumpy days westwards. The road led along the northern Sichuan- Tibet Highway to the small provincial town of Ganzi. Here was the last stop before the mountains where our local support crew, translator Alex and cook Pan bought the last supplies for base camp. From the roof of our hotel, we could already see the towering mountain of the central Ganga, and its highest peak ….. Well, what was its name? Our permit, formally given by the Chinese Mountaineering authority, the peak was defined as Mt Wuming (?!), but this was just a placeholder the authorities use for every peak that doesn’t have a name. As one could see the peak from almost everywhere in town I thought it impossible that it hadn’t got a name – equipped with the chinese phrase of (“Whats the name of this mountain?”) I went through town interviewing people and had to realize: a) there weren’t a lot of people in town that speak chinese – culturally this part of Sichuan belongs to Tibet, and most people I met didn’t want to write or speak Chinese b) that my questions tons usually ended in a ton of laughter or utter confusion c) and that only a very old woman, after a lengthy discussion (the topic of which I would obviously not know, as it was in a language unfamiliar to me) scribbled the word “Zhouda” into my notebook. So there we were – on our route to Zhouda-shan (Mt Zhouda).  Base Camp was pitched in a deep valley, with steep scree slopes rising left and right towards the mountains. Establishing a higher camp was a big pain. A huge loadback (my backbag must have been 25kg or more) had to be carried up a very steep slopes of loose rubble and rocks, not funny – every 2 steps up were followed by gliding more than one step down…little did I know then, that over the course of the expedition I would need to climb theaw slope more five times!! Looking up from high camp we had an amazing view into the majestic south-east face of Zhouda, where we identified two possible routes. A classic rock climb through the center of the face and a snow gully further to the left.

Base Camp was pitched in a deep valley, with steep scree slopes rising left and right towards the mountains. Establishing a higher camp was a big pain. A huge loadback (my backbag must have been 25kg or more) had to be carried up a very steep slopes of loose rubble and rocks, not funny – every 2 steps up were followed by gliding more than one step down…little did I know then, that over the course of the expedition I would need to climb theaw slope more five times!! Looking up from high camp we had an amazing view into the majestic south-east face of Zhouda, where we identified two possible routes. A classic rock climb through the center of the face and a snow gully further to the left.  Before we even could attempt it, heavy snow fall during the night thwarted our ambitions and which meant the whole team was back down in base camp, waiting for better conditions – pattern we would get familiar with in the following days. Almost every day brought some form of precipitation, rain, hail and higher up tons of snow… the dry periods in between were rarely long enough to dry to the wall out. Meanwhile we were idling in base camp, enjoying the awesome, super spicy meals prepared by Pan & Alex (“Old dry Mama” a local chili paste became the favourite ingredient). Ed and Rob were finding ever more innovative ways to make proper coffee, and I was slowly but surely running out of books on my Kindle.

Before we even could attempt it, heavy snow fall during the night thwarted our ambitions and which meant the whole team was back down in base camp, waiting for better conditions – pattern we would get familiar with in the following days. Almost every day brought some form of precipitation, rain, hail and higher up tons of snow… the dry periods in between were rarely long enough to dry to the wall out. Meanwhile we were idling in base camp, enjoying the awesome, super spicy meals prepared by Pan & Alex (“Old dry Mama” a local chili paste became the favourite ingredient). Ed and Rob were finding ever more innovative ways to make proper coffee, and I was slowly but surely running out of books on my Kindle.  Spotting a small weather window we decided to skip high camp and start directly, super early out of base camp for a second try. By lunchtime we had reached the final wall, the sun was heating down and the scree slopes were as painful as ever. The snow in the gully was of dubious quality – we had to rope up pretty soon, pitch after pitch going higher, most of the time protection was difficult to place… by late afternoon clouds were covering the sky, while our progress came to a halt, a waterfall of rotten (ie really easy splittery ice) was blocking our way- no way onwards. To accelerate our decision making process a loud “BOOOM” was thundering through the valley – thunderstorm! …. as fast as safely possible (but still painfully slow) we rappelled down into the darkness of the night, our headlamps lighting up the heavy snowfall. By the time we reached our tents we had been climbing continuously for 15 hours and everybody felt shattered!

Spotting a small weather window we decided to skip high camp and start directly, super early out of base camp for a second try. By lunchtime we had reached the final wall, the sun was heating down and the scree slopes were as painful as ever. The snow in the gully was of dubious quality – we had to rope up pretty soon, pitch after pitch going higher, most of the time protection was difficult to place… by late afternoon clouds were covering the sky, while our progress came to a halt, a waterfall of rotten (ie really easy splittery ice) was blocking our way- no way onwards. To accelerate our decision making process a loud “BOOOM” was thundering through the valley – thunderstorm! …. as fast as safely possible (but still painfully slow) we rappelled down into the darkness of the night, our headlamps lighting up the heavy snowfall. By the time we reached our tents we had been climbing continuously for 15 hours and everybody felt shattered!  Again bad weather bound us to doing nothing.. so we used the time to find a new approach. An exploration towards the north face (with an SUV “borrowed” from the local mining company) brought no real solution, but a walk towards the west ridge the day afterwards led us into a fantastic new valley, with a crowning south face at its end… it looked way more approachable than everything else we had so far spotted on the peak. The next morning (very early), the team again started from high camp – the weather looking very good. But yet again our attempt came to stuttering halt: Strong wind was blowing rocks (up to the size of a football) down the face and we literally ended up in a grenade shower, with impacts left, right and center! With the closest hospital being more than 750km away, there was no risk to take, and we aborted…. Back to base camp once more, now even more frustrated. Was there enough energy left for a last attempt – yes there was! One last time the team pulled all the strength together, by early morning we were at the bottom of the wall reaching our previous high point before lunch.. The going was good, fast and the snow and ice was in much better condition, however by no means easy – (Rob’s comment: “These were the most dicy pitches I ever lead”) – we were pushing higher, reaching the upper end of the gully. Then, as if the mountain would feel that these climbers were on its route to the top, again heavy clouds were starting to engulf the peak. Hail, then snow, heavier and heavier. At the same time we realized the gully we were following was hitting a dead end… at an altitude of 5330m we called it a day. Ed and Rob had reached the top of the last pitch, there was no way higher… with the snowfall getting more and more it was time to get out! Big chunks were coming down (I counted more than twenty hits on my helmet and one in the face that left me with bloody lips and nose) Not without frustration we started to rappel, while spindrift avalanches were coming down the gully! Thankfully a few hours later we all safely reached our tiny tents at high camp. We had given everything – explored several new valleys, walls, came a bit too close with nature and made it almost to the top. But we kept with Hillary’s saying: Getting to the summit is optional, getting down is mandatory””

Again bad weather bound us to doing nothing.. so we used the time to find a new approach. An exploration towards the north face (with an SUV “borrowed” from the local mining company) brought no real solution, but a walk towards the west ridge the day afterwards led us into a fantastic new valley, with a crowning south face at its end… it looked way more approachable than everything else we had so far spotted on the peak. The next morning (very early), the team again started from high camp – the weather looking very good. But yet again our attempt came to stuttering halt: Strong wind was blowing rocks (up to the size of a football) down the face and we literally ended up in a grenade shower, with impacts left, right and center! With the closest hospital being more than 750km away, there was no risk to take, and we aborted…. Back to base camp once more, now even more frustrated. Was there enough energy left for a last attempt – yes there was! One last time the team pulled all the strength together, by early morning we were at the bottom of the wall reaching our previous high point before lunch.. The going was good, fast and the snow and ice was in much better condition, however by no means easy – (Rob’s comment: “These were the most dicy pitches I ever lead”) – we were pushing higher, reaching the upper end of the gully. Then, as if the mountain would feel that these climbers were on its route to the top, again heavy clouds were starting to engulf the peak. Hail, then snow, heavier and heavier. At the same time we realized the gully we were following was hitting a dead end… at an altitude of 5330m we called it a day. Ed and Rob had reached the top of the last pitch, there was no way higher… with the snowfall getting more and more it was time to get out! Big chunks were coming down (I counted more than twenty hits on my helmet and one in the face that left me with bloody lips and nose) Not without frustration we started to rappel, while spindrift avalanches were coming down the gully! Thankfully a few hours later we all safely reached our tiny tents at high camp. We had given everything – explored several new valleys, walls, came a bit too close with nature and made it almost to the top. But we kept with Hillary’s saying: Getting to the summit is optional, getting down is mandatory””  The next day Gerald, Judith and myself embarked on a last exploration mission towards the south-west ridge to collect as much data for future expeditions – we managed to climb a coloir (the “Austrian- coloir”) up to 5230m , where we fixed some Tibetan prayer flags. All that was left for us was to pack our bags, carry it back (through a super cold icy river) and drive back towards civilization.

The next day Gerald, Judith and myself embarked on a last exploration mission towards the south-west ridge to collect as much data for future expeditions – we managed to climb a coloir (the “Austrian- coloir”) up to 5230m , where we fixed some Tibetan prayer flags. All that was left for us was to pack our bags, carry it back (through a super cold icy river) and drive back towards civilization.  The summit eluded us this time, but there will be another time! I am lucky to have been part of such an adventure with a great team in an amazing area. There are areas, valleys and mountains to explore for a lifetime!

The summit eluded us this time, but there will be another time! I am lucky to have been part of such an adventure with a great team in an amazing area. There are areas, valleys and mountains to explore for a lifetime!

The curse of the mosquito (or being caught out by climate change)

The plan was straightforward: Pack bags, travel to remote valley, hike to virgin peak. Climb! So was the plan for my recent expedition into the remote Naar-Phu valley in Nepal, which came together...