The plan was straightforward: Pack bags, travel to remote valley, hike to virgin peak. Climb!

So was the plan for my recent expedition into the remote Naar-Phu valley in Nepal, which came together on short notice. But just when you think its simple, it always turns out way different.

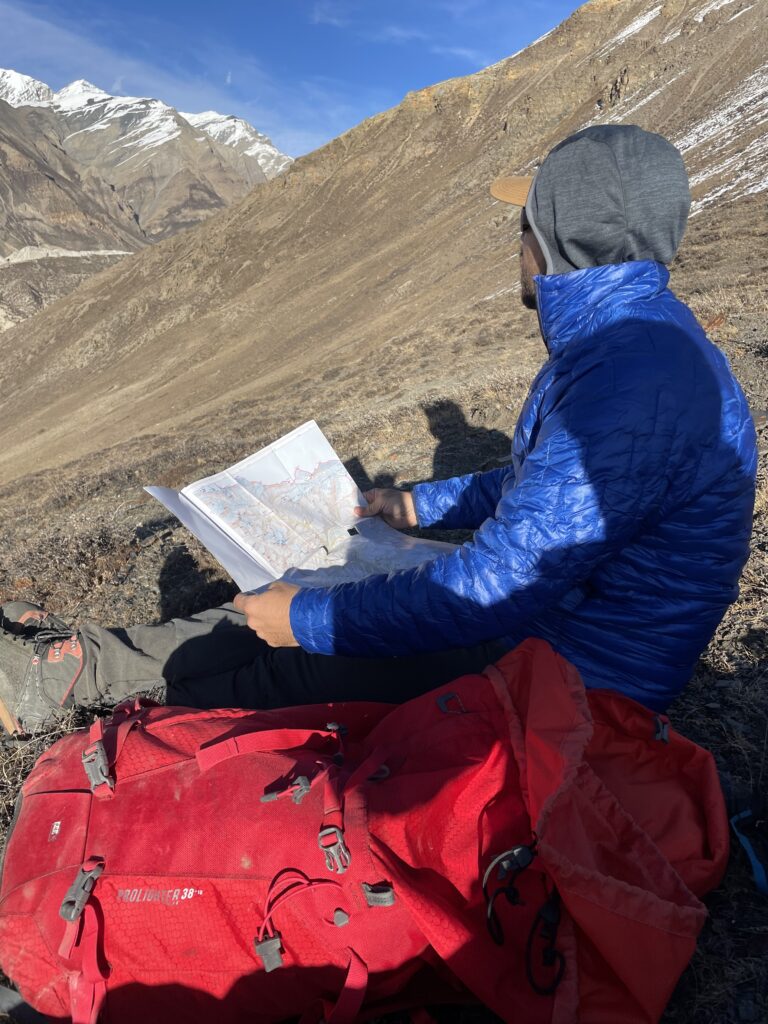

Being off limits for trekkers until a few years ago, the area is still very much off the beaten track. While we started with delay (an unexpected night on the way to the trailhead) as soon as were trekking up the remote valley of the Peri Himal I felt in in different world. After several days the snow-capped summits of our goal started to appear. Climbing virgin peaks is not a definitive art – there is no central register, most of the time it’s only a summit cairn that reveal whether there has been human presence there before. A small base camp for our four-man climbing team was built up near the Ratna Chuli basecamp. I felt great and was ready to climb – until I wasn’t.

Day 1 in Basecamp: I wake up with a severe headache. I feel so tired! Probably the altitude. I take rest.

Day 2: I feel even worse (albeit slightly). All I want is sleep.

Day 3: I take a few painkillers and accompany the rest of my team on a scouting hike. We get up to 5500m, but I feel like I had been partying for 72hrs non-stop. I feel so empty. Absolutely depleted.

Day 4: My throat is coarse, my joints ache, I don’t want to leave my sleeping bag (anyway it was -10C overnight and it had snowed a bit). I find a thermometer –39.7C !

Day 5: The fever is still high; I am shivering and I am absolutely spent – only a pain killer brings some temporary relief. Something is seriously wrong here.

Day 6: I cannot really leave my tent. I am stuck in my sleeping bag, I know I need medical attention, soon!

Night 6/7: It’s time to call it quits. Following efforts of my wife who I had notified by Sat phone, my teammates call the helicopter, they sacrifice their summit attempt (as it turns out the only chance they had) to get me evacuated. It’s a no-fly area, so it needs special approval – it takes a long time until I can move my absolutely tired body. 2hrs later I am in Kathmandu. Diagnosis: Dengue Fever!

How on earth did I get a tropical fever on a Himalayan expedition?

The idea of the expedition might have been simple, but we live in a complex world, which seems to get more volatile and unpredictable every day. Especially climate change is wreaking havoc with our way understand the world and plan for certain events.

Turns out that my expedition coincided with the most severe outbreak of Dengue Fever in recorded Nepali history. Dengue is transmitted by the Aedes mosquitoes, and while they used to die on altitude, less cold nights mean they now survive much higher up. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world’s leading authority on climate science stated, “at high elevations in Nepal, there is high confidence that climate change has driven the expansion of vector-borne diseases that infect humans.”

Climate change had caught up with me – it wasn’t rockfall or melting glaciers, effects of climate change that mountaineers are aware of. It was a mosquito!

While we had engulfed in proper planning, had built a rescue chain, had discussed eventuality we had not calculated with tropical fever. Thankfully, when preparing for an expedition, I keep it German general Moltke the Elders famously credo: “No plan survives contact with the enemy”.

Indeed, as unexpected risks, black swans and volatility cause disruptions in complex systems we need to increase two things:

Adaptivity & Resilience

These abilities allow us to adjust to changing circumstances and to recover from difficulties. We can do so by:

• Flexible Planning and preparation. Having a clear research question, a realistic budget, a detailed itinerary, a risk assessment, and a contingency plan, before we embark on an adventure. Research the site, the culture, the weather, and the potential challenge. Planning and preparing can help anticipate and avoid problems, or deal with them more effectively. And always add some buffer!

• Absorb and adapt. These are types of resilience capacities that can help achieve goals in spite of shocks, stresses, and uncertainty. Absorptive capacity is the ability to minimize the impact of a disturbance by using available resources and coping strategies. Adaptive capacity is the ability to adjust your behavior, practices, or structures in response to a disturbance or opportunity.

• Learn and reflect, or as I call it Post-Mortem Analysis. Take time to review what went well and what didn’t, and what was learned from the experience. Seek feedback from others and share your insights and best practices. Learning and reflecting can help improve skills, knowledge, and confidence for future.

All these added risks shouldn’t mean that we stay at home. Just as I write these lines I hear the waterbomber overhead trying to extinguish a forest fire a few kilometres away. Our life is full of risks.

No, we need to venture out and explore – but we should do with resilient and adaptive planning.